Deep Dive

The Narrative Toolbox for Level Designers

December 6, 2022

Video Essay

Abstract

Level designers are the architects of game worlds, and so they play a large role in conveying the narrative of a game. However, they have many tools at their disposal to convey different types and aspects of a story.

Some game projects start with high-level narrative beat that their levels must communicate, which can help guide their design decisions throughout, ensuring their story stays cohesive and is communicated as intended throughout the experience.

Each subsequent level in a game makes up the narrative structure, and to keep each level interesting, each should have a self-contained narrative structure.

Emotion and theme charts can be used to plan out the desired effect of every moment of a level, allowing designers to flesh out the high-level effects of their level before any effort is spent deeper in production, when changes are harder to make.

Once creating the level geometry, designers gain access to the whole narrative delivery toolbox. This article illustrates many tools that can used during this process, including planning out the inclusion of cutscenes and dialogue, using environmental storytelling to convey small aspects of a larger world, and using level geometry to convey the desired emotion. Furthermore, this article will investigate how artistic devices seen in other media such as cinematography and contrast can be used in interactive experiences.

Finally, this article will investigate how to work within a large multi-disciplinary team to build great levels that fit cohesively with the rest of the world and production.

Introduction

When building a game with a heavy focus on narrative, the story seeps into every aspect of the project. One thing has stuck out across all my research while conducting this deep dive, that the narrative is more than just the script. All aspects of a game can used to communicate parts of the narrative and one of the strongest mediums of storytelling within games is level design. Therefore, the job of level designers on these projects is slightly different than it is on less narratively focused projects. Level designers tend to take on an additional role of narrative designer or storyteller, as they design their levels to meet a narrative goal. Games from across the genre and budget spectrums have approached and tackled the challenge of communicating the narrative through their level design in many ways. From high level guidelines given to designers in projects like The Last of Us, to tools like using level geometry to evoke emotions, this deep dive will examine exactly how level designers can and should take on the role of storyteller on narrative-heavy game projects.

High Level Approaches

In the early stages of level production, narrative should be at the forefront of the designer’s mind. Whether the specific narrative beats for the level come from the game’s director like in The Last of Us (Brown 2020) or are discovered while fleshing out the scenario like in Mass Effect 3 (Feltham 2013), levels in narrative games are built upon the desired narrative and gameplay outcomes of the level.

Narrative Beats

In the 2020 video, “Making The Last of Us Part II’s Best Level” by Game Maker’s Toolkit, Mark Brown interviews The Last of Us Part II level designer Evan Hill about the creation of “The Birthday Gift” level. Hill states that the initial direction given from the game’s director was a select few narrative and gameplay beats, which were:

1. Joel taught Ellie how to swim

2. There’s a thing in the museum where [Joel and Ellie] confront each other about the Fireflies

(Brown, 2020)

Peter Field, a level designer on The Last of Us published a YouTube video in 2020, breaking down the Bus Depot level, which he designed. Peter lays out how Naughty Dog approached the early stages of the level design - by describing its necessary narrative and gameplay beats.

Peter describes the beats as:

1. Show Ellie’s Depression

2. Wild Animals

3. Joel sees toll of journey on Ellie

4. Ellie determined to reach fireflies

(Field 2020)

This idea of high-level beats being given to level designers is echoed throughout the game development industry, with The Last of Us franchise, Horizon: Forbidden West, and Mass Effect 3 as just a few examples where this approach has been utilized. The 2017 game Rime is almost entirely designed around this idea, with each area being based on a different stage of grief. The game speaks (or doesn’t speak) in metaphors, with the main communicator of the themes being the level design itself.

These major beats are typically laid out in the early stages of the project’s development when the story is being formulated. For example, Evan Hill stated that he got the required beats for his Last of Us Part II level early on from Neil Druckmann, the game’s director (Brown 2020), and on Horizon: Forbidden West, these beats were developed and locked down by the narrative team and creative director (Francis 2022). By writing the entire game as beats early in the process, the narrative team has a way to ensure their masterfully crafted story is communicated throughout the game. These beats are essentially the most important things the level needs to communicate, and it’s now the level designer’s job to figure out how best to communicate them.

Essentially, the necessary narrative and gameplay beats for each level given by the narrative team guides the level designers through their design and helps ensure that the entire game’s narrative will be cohesive and complimentary, working towards the overarching narrative goal.

Three Act Structure

The three-act structure is a well-known narrative structure used in many of the most famous stories. In games, the three-act structure is of course also applicable to the overarching story, but also applicable to individual levels and their pacing. When creating a mission or level within a game, the three-act structure can be utilized to create a well-paced, evocative sequence of events and accompanying gameplay.

This structure was utilized in Mass Effect 3’s Genophage Level as follows:

· Act 1

o Inciting Incident – Reaper at the Shroud

o First Reversal – Highway Crash

· Act 2

o Low Point – Wreav Dies

o Second Reversal – Use Kalros

· Act 3

o Climax – Cure the Genophage

o Epilogue – Funeral

(Feltham 2013)

So sure, the story of the level can follow the three-act structure, but so should the level and mission design. As a part of creating the ups and downs of the three-act structure, Dave Feltham, a level designer on Mass Effect 3, said, “You start below the Reaper, you’re overwhelmed … but then we actually push you through the level, and bring you up to the same height as him. Nope, you can do this. Make the player feel confident. We actually make the player want to jump over the gap. And then that’s the immediate time that we actually pull the rug from under you – literally – and you fall down and then you’re below, feeling overwhelmed by this Reaper that is towering over you,” (Feltham 2013). Even with almost just the level geometry, Mass Effect 3’s designers created almost a literal representation of the three-act structure. This use of the three-act structure is seen in many other titles, including the indie gem, Celeste.

The player’s literal elevation during the climb up Celeste’s Mountain mirrors the three-act structure (Brown, “How Level Design Can Tell a Story” 2020). As you make your ascent, you meet occasional setbacks, and places that you must do a bit of downwards climbing, but you’re overall making constant progress towards the peak. That is, until about halfway through the game, where you are sent crashing down, all the way to the bottom. Then, with newfound abilities and hope, you make your ascent all the way to the peak, reaching the climax. This structure of the game works excellently to keep players engaged throughout the experience and keep them wanting to move onward and upward.

Essentially, level designers have access to the same narrative structures seen in other mediums and can use them in creative ways throughout the level design process to plan and pace not only narrative, but also gameplay.

Emotion & Theme Charts

Emotion is a powerful storytelling tool that transcends language barriers. As the most interactive storytelling medium, games have a unique opportunity to utilize emotion. Level designers can use scale, shape, color, and more to evoke emotions out of players with their level geometry alone.

Emilia Schatz, speaking on Uncharted 4, said “If I want to have the player feel triumphant at the end and scared towards the beginning, I might make the environment create a lot of pressure on the player, I might make the ceiling very low, I might make the walls come in so you feel tight and constrained, and eventually we sort of, as we get to the end, bring you out way into the open and give you this giant vista. That gives you the emotional contrast, the flip of values from being confined and scared, to being triumphant…” (Critical Path 2018).

But how do we figure out what themes and emotions our levels should be evoking? Well, Dave Feltham shares the idea of an Emotion & Theme Chart. The chart is simple, but effective, describing the desired theme and emotion for each area of the level (Feltham 2013).

|

Level Area |

Theme |

Emotion |

|

Area 1 |

Theme |

Emotion |

|

Area 2 |

Theme |

Emotion |

The themes and emotions that are slotted into these fields can come from a variety of places. Some of them will be obvious based on the desired narrative beats of the level, while others could be found with things like the three-act structure.

For example, if the narrative beats you were given for a level were:

1. Illustrate father-son relationship

2. The father loses track of the son

3. The son is found tending to an animal with a mysterious woman

Then the Emotion and Theme chart could start like:

|

Level Area

|

Theme |

Emotion |

|

Forest Clearing |

Father/Son Relationship |

Empathy |

|

Ravines |

Parental Panic |

Panic, Anxiety |

|

Injured Animal |

Relief and New Developments |

Relief, Hope, Curiosity |

These beats are actually derived from a level from God of War (2018), where while hunting, Atreus (the son) runs off forward into potential danger, while Kratos (the player and the father) must catch up and ensure his safety. The level then takes players into a ravine, with tight pathways, plenty of fog, and the golden path often leading to dead ends. All these level design decisions were based around evoking the theme of parental panic, and the emotions of panic and anxiety. By deciding the theme and emotion throughout a level before committing to any geometry, designers can ensure that their levels are paced well, meet the required story beats, and can then use the themes and emotions as guidelines from which to build the geometry and gameplay for their level.

The Narrative Delivery Toolbox

Figure 1: (Menzel 2017)

Games, as an interactive storytelling medium, have lots of different opportunities and methods to deliver narrative. These include environmental storytelling, dialogue/gameplay choices, cutscenes, quick-time-events (QTE’s), and various types of triggered dialogue. Each of these methods provide a different amount of agency and have a different amount of certainty that it will be delivered to each player, as depicted by Figure 1 (Menzel 2017).

Although the exact content of each of these storytelling events within the game will likely eventually be created by other teams such as the narrative team and/or art team, the level designer can and often should be thinking and planning when, how, and why each storytelling method is used.

Cutscenes

Cutscenes provide the most certainty that a particular narrative moment will be communicated to the player, and so they should often be used for most important narrative moments in a level. However, Menzel’s graph seems to imply that all cutscenes take place along the linear path of the level. This is a very limiting assumption about cutscenes, when they can and have been used in optional side content to communicate narrative beats that would be impossible to do within regular gameplay.

The Last of Us Part II expertly utilizes cutscenes in multiple ways throughout the game, when its story calls for communicating something the characters do that the player doesn’t or shouldn’t have control over. In “The Birthday Gift” level, a cutscene is used when Ellie and Joel enter the cockpit to illustrate the connection between Joel and Ellie and to communicate how Ellie felt at this moment in time. The cutscene utilizes effective cinematography principles, unique animation, and great sound design to create an experience for the player that wouldn’t be possible within the regular gameplay. In cutscenes, there is also the opportunity to include QTE’s which can increase the agency the player feels between themselves and the character’s actions, even when in a cutscene. However, a moment like the cockpit is so delicate that a QTE would probably have only hurt it. Though, earlier in the same level, a QTE is used to great effect, as after a non-interactive cutscene when Joel pushes Ellie (the player) into the water (which turns into a swimming tutorial and accomplishes one of the required narrative beats for the level), Ellie later gets a chance for revenge as the player gets to press a button to push Joel into the water (Brown “Making The Last of Us Part II’s best Level” 2020). This small interaction included within the cutscene helps build the player’s connection with Ellie as everyone understands why Ellie would do it, and they probably want to do it themselves too.

Cutscenes can also be used as optional side content, providing more narrative delivery to players that take the time to explore. Last of Us Part II contains an optional cutscene in a music store, where Ellie plays an acoustic rendition of Take On Me. The important part in something like this for level designers is not how effective the cutscene is, but rather looking at how this cutscene was planned in the level design. From designing the environment to be contextually appropriate for the cutscene idea, to designing the space with bonus areas that promote exploration, the level designers played a big role in delivering this narrative moment to players.

Despite being pretty far outside of the responsibilities of a level designer, cutscenes are a crucial part of conveying the narrative in many games. Most cutscenes also take place contextually within a level, making planning when, where, and why a cutscene is needed a crucial tool in a level designer’s toolbox.

Dialogue

Although level designers are typically not the ones writing it, dialogue is an effective narrative tool that can be implemented in many ways. From enemy shouts to audio logs, to walk and talk sequences, to direct conversation, level designers can utilize this storytelling method by planning for it when mapping the space.

Geoff Ellenor’s 2022 article Storytelling for Level Designers illustrates how he uses primitive methods to prototype narrative delivery. He will read placeholder dialogue out loud while walking down a grey box hallway to check if there is enough time for characters to say what they need to say (Ellenor 2022).

Environmental Storytelling

The spaces we exist in daily tell a story about us, whether we like it or not. When building a game world, these context clues that suggest who was here, what they were doing, where they are or where they went, when this was, why this happened, and how it happened, can work as a storytelling method in and of itself.

In a 2010 GDC talk, Hervey Smith and Matthias Worch defined the term as “Staging player-space with environmental properties that can be interpreted as a meaningful whole, furthering the narrative of the game.” The term, also called diegetic storytelling, often means building spaces that somehow illustrate something that happened in it before you got there. The skeletons being in all kinds of funny poses in Fallout, the sequence near the beginning of The Last of Us where a bunch of citizens are lined up on their knees for an infection test, and the eventual police investigation at shops where you killed the shopkeeper in Deus Ex: Mankind Divided are all examples of how the concept of environmental storytelling can be used, twisted, and experimented with (Brown, “How Level Design Can Tell a Story” 2020).

Another narrative delivery method under the environmental storytelling umbrella is journal entries, captain’s logs, emails, and other discoverable notes from a previous time. These can provide a clearer picture, and a personal point of view of events. These types of notes are likely out of a level designer’s responsibilities, but by using other environmental storytelling options, and designing in spaces for secrets to be found, level designers can take some control over this tool and add it to their toolbelt.

An interesting thing about environmental storytelling is that it forces the player, not their character, to solve the question of what happened in this space. As Mark Brown of GMTK puts it, “This makes us an active participant in the storytelling process, and not just a passive viewer,” (Brown, “How Level Design Can Tell a Story” 2020). This makes it a very interesting type of narrative delivery, but one that needs to be thought of differently than most others. This type of gameplay could constitute an entire game on its own, but if it’s not the game’s main mechanic, then designers need to be careful not to hide key information behind the prerequisite of piecing together what happened, at least on their own. Many games feature detective mechanics, where the player must investigate crime scenes and the like, such as Batman: Arkham Knight and Horizon: Forbidden West, but because it is not the main focus of either game, the systems greatly assist the player with things like highlighting clues and having the character piece together what happened, rather than the player.

As is evident from Menzel’s graph (Figure 1), environmental storytelling has a ton of player agency associated with it, but it also has a high chance of being missed by many players. This makes it a great tool to make worlds more believable, interesting, and just to add more things for the players to find and discover, but not the right tool to communicate key narrative points in most games.

Emotion / Mood

As mentioned earlier, games can evoke powerful feelings in players with nothing more than a space to interact with. Using the same principles used in film, photography, and other visual mediums such as shape, scale, color

If the narrative calls for the player to feel powerful and hopeful, then putting them high above the rest of the world might be a good idea. In contrast, if the narrative calls for a moment when the odds should feel impossible, then putting the player at the base of whatever challenge they need to overcome, making them feel small in comparison, might achieve just that.

An excellent example of this is the game Rime where you physically play through each stage of grief. Each level is designed to evoke the emotions and feelings associated with a key stage in the journey towards acceptance of a loved one’s death. One of the most obvious relationships between emotion and level design is in the “Anger” stage. In it, the big metal ball the player needs to complete the puzzle that opens the door to the next area is stolen by a big, angry, and unapologetically violent bird. This bird then hounds the player as they move through the level, not letting them be out in the open for more than a few seconds before insta-killing them. This means the player must completely change their playstyle to be inefficient, darting from cover to cover to stay out of sight of the bird. This oppression builds a sense of anger within the player, just as humans go through a stage of anger in their journey towards acceptance. A more subtle level is the “Bargaining” stage, where the player plays through a series of puzzles and areas meant to embody the different ways the bargaining stage embodies itself in people. The level features a door puzzle that represents how people try new things in an attempt to feel better but just end up back where they started, an endless hallway that forces you to stop trying to push forward and instead look backwards to move on, and a construct companion that you help, and in turn helps you move forward. Rime is a special case as it attempts to communicate its narrative almost entirely with its level design in a metaphorical world that doesn’t need to constrain to an overarching setting or society and so its communication is likely too literal for many games, but the principles it uses to communicate its themes are certainly worth studying.

As illustrated by David Feltham, it is crucial to test that your level is meeting the desired emotion, which he uses the Emotion & Theme chart for (2013). In playtesting, developers can ask testers what emotions they were feeling during the different sections of a level. These responses can then be compared to the desired emotions and themes from the initial plan, and then changes can be made if needed to the specific areas in the level.

Cinematography

Levels can leverage the cinematography principles seen in other forms of media to create powerful interactive experiences. Whether it’s creating forms that create fantastical compositions with the regular gameplay camera, or shifting the camera angle for a specific level such as in Roki. Alex Kanaris-Sotiriou, in a deep dive into Roki’s approach to storytelling, illustrates how they decided to stick the camera within the trees, undergrowth, and rocks that make up the deep forest setting. They anchored the cameras to one location at a time, only turning to look at the player, as if something unseen is watching them (Kanaris-Sotiriou 2021). This is a cinematography tool seen often in other mediums like films, but it’s implementation in a game, when mixed with the interactivity, creates an even more harrowing experience, evoking strong feelings from the player without saying a word in dialogue.

Contrast

Continuing on the discussion of Roki, Alex Kanaris-Sotiriou (2021) wrote,

“…in a story you also need space for ‘no-story’. Many creative endeavors generate interest from contrast; whether it's a painting, music, film, or games. Contrast attracts the eye, ear, and mind and also gives texture to an experience. In games, giving breathing space within a game’s narrative can give the player a chance to reflect and absorb the events of the game and allow its themes to take root in their minds and resonate with their own life experiences.”

Using contrast between action and quiet moments, tight corridors and open plains, or even between the colours used can evoke emotions in players and create personal moments of reflection that the developers could never imagine the extent of. Contrast can be created with almost any of the tools described so far, and looks to further the desired emotion of the any of them. Sure you could just give the player an open world from the start, but first tightly limiting their space, then opening the world up will enhance their feeling of freedom seen in games such as Skyrim (2011).

Communicating Narrative Through the Space

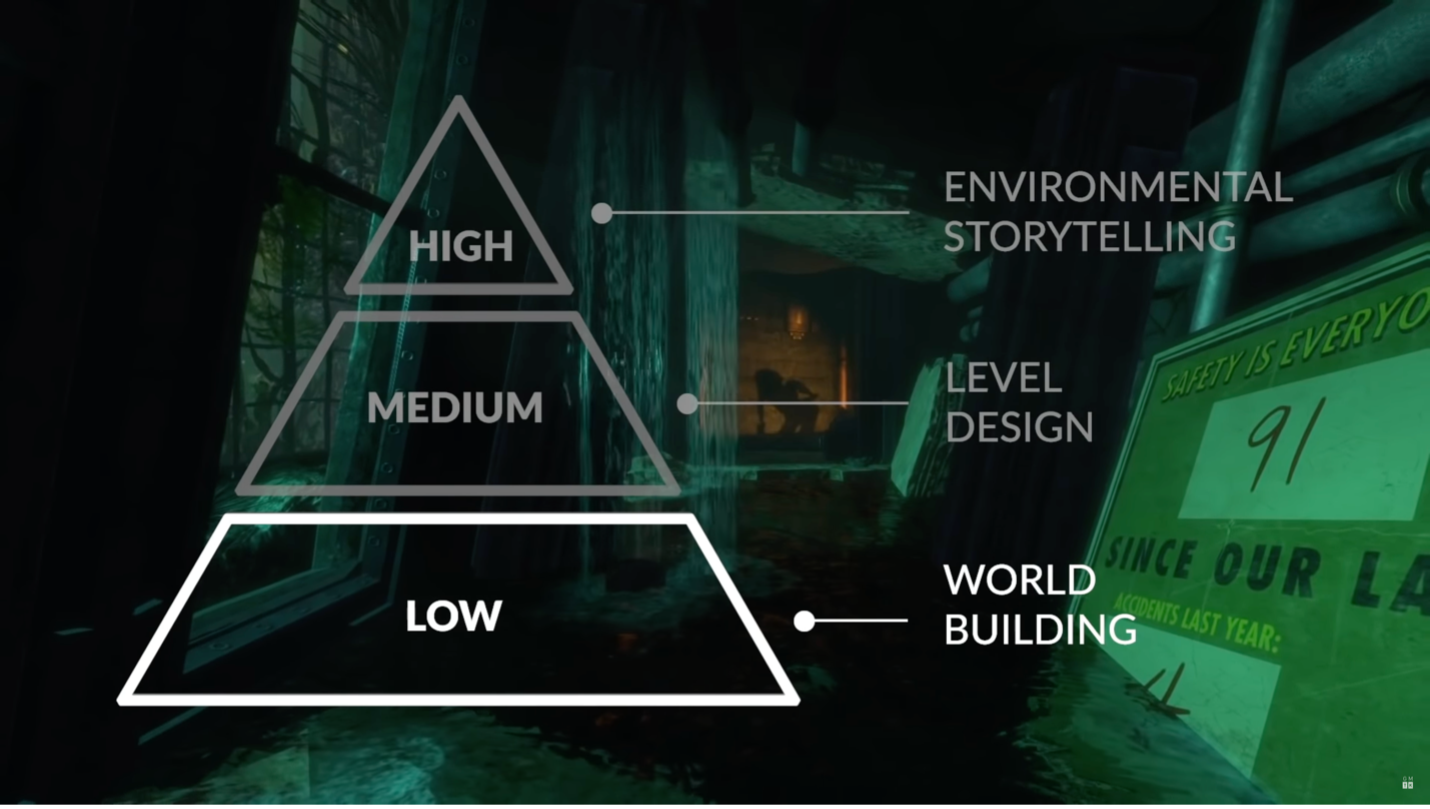

Figure 2: Pyramid chart depicting different types of narrative delivery that can be utilized by level designers (Brown “How Level Design Can Tell a Story,” 2020)

The spaces games exist within tell us a lot about the world and the people that inhabit it. Tight corridors, like those in Half-Life 2, could communicate oppression and lack of freedom, while wide open fields, like those in Horizon: Forbidden West, could communicate a sense of freedom and venturing into the wild. Mark Brown, in his GMTK video “How Level Design Can Tell a Story” (2020), shares a graph (Figure 2) that depicts the different levels of narrative delivery that level designers can utilize.

The graph is shaped like a pyramid to depict the scale and relationship between the different types of narrative. Brown suggests that environmental storytelling is a high-level type of narrative delivery, and it usually the most literal and easily read type of narrative delivery within levels. These small dioramas that exist within the larger world are informed by both the designed spaces and the overarching world building. Moving onto Level Design, which Brown, in this case, refers to as the literal spaces built by the level designers, it can be used to communicate larger scale interactions between people in the world. Brown shares the example of Dishonored 2’s Dust District, where the level designers put the lower-class districts specially below the higher classes. These types of spacial relationships between and within spaces are powerful tools that can communicate a ton about the world without having to say a word.

The 2022 game Stray uses a similar structure, with the feline protagonist starting on “the surface” before falling all the way down to the bottom floor of a subterranean, multi-floored robot society. As you make your way back up floor by floor, it becomes clear, that each floor, and its inhabitants, seem to rise in class and order.

World Building then means the overarching story of the world, the broadest strokes, created by the narrative designers (Brown “How Level Design Can Tell a Story,” 2020). Brown (2020) highlights the importance of ideas flowing from the top to the bottom, and back again. This collaboration between level designers and the narrative designers is a key part in making a world feel real and cohesive, from the overarching idea of the world to the layout of someone’s bedroom.

Organizing The Process

Geoff Ellenor’s 2022 article “Storytelling for Level Designers” illustrates how to approach storytelling within a level in a AAA studio. The big thing Geoff highlights is about how to get your overall vision for the level communicated and documented early (Ellenor 2022). This is because of the large size of AAA teams, containing level designers, artists, writers, techs, and more, all of whom need to get on the same page to build a great level (Ellenor 2022). Geoff calls this design, “Macro Design,” where you would lay out the large narrative and gameplay beats for the level (Ellenor 2022). Geoff gives the example of “vigilante hero arrives at a mad scientist’s lab and investigates to find out what Dr. Badguy is up to,” (Ellenor 2022). It is important to ensure everyone on the team is aligned on the level’s intention as it is up to the level designer to deliver the desired experience and they can’t do it without the rest of their team. Geoff’s next step is to design and describe the beats of the level, which more specifics like “once investigating, the player gets an objective to ‘search for clues’,” more thoroughly (Ellenor 2022). Greyboxing should also serve a big role in developing the level and storytelling methods. Geoff talks about how he uses primitive methods to prototype narrative delivery like reading placeholder dialogue out loud while walking down a greybox hallway to check if there is enough time for characters to say what they need to say (Ellenor 2022). Geoff also talks about the importance of the greybox being a part of your documentation, with the greybox itself, gameplay videos, and photos all being documented as references for the level and desired experience going forward (Ellenor 2022). Geoff also describes various other storytelling tips for level designers such as leaving space for character reactions, giving reminders of key information, and linking big story moments with the biggest challenges (Ellenor 2022).

Conclusion

So, when a level designer is starting on a level in a game that features a narrative, they have many tools at their disposal to convey different types and aspects of a story. They could start with high-level narrative beat that their level must communicate, which can help guide their design decisions throughout, ensuring they are communicating what they need to by the end of the level. A level should know it’s place within the overarching narrative structure of the game and have a narrative structure itself. The three-act structure is one of the most common and successful structures, creating undulating rise and falls throughout the experience, balancing feelings of hope and despair. Designers can use emotion and theme charts to plan out the desired feeling for each part of the level, giving them a stronger guide when they jump into greyboxing. Once they get to greyboxing, the whole narrative delivery toolbox becomes available to them, from planning out the inclusion of cutscenes and dialogue, using environmental storytelling to convey small aspects of a larger world, and using level geometry to convey the desired emotion. Designers can even use artistic devices seen in other media such as cinematography and contrast to create memorable interactive experiences. The spaces that designers build fit into a larger world, and so they must funnel the overarching ideas of the narrative team into small dioramas of the world that convey specific aspects. This process should involve plenty of collaboration between all the teams on a game project, which means that getting buy in from everyone early is key to a successful level.

Works Cited

Batman: Arkham Knight [Video Game]. (2015). Rocksteady Studios.

Brown, M. [Game Maker’s Toolkit]. (2020, March 11). How Level Design Can Tell a Story

[Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RwlnCn2EB9o&t=71s

Brown, M. [Game Maker’s Toolkit]. (2020, Aug 3). Making The Last of Us Part II’s Best Level

[Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KW4JlxAEAE0

Critical Path (2018, November 12). Ask a Developer: Emilia Schatz Talks Level Design [Video].

YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CRDaXvkge8Y

Deus Ex: Mankind Divided [Video Game]. (2016). Eidos Montreal.

Ellenor, G. (2022, March 20). Storytelling for Level Designers. Medium.

https://gellenor.medium.com/storytelling-for-level-designers-221a4e94bf59

Feltham, D. (2013). Emotional Journey: BioWare’s Methods to Bring Narrative into Levels

[Video]. GDC. https://www.gdcvault.com/play/1017761/Emotional-Journey-BioWare-s-Methods

Field, P. (2020, June 8). The Last of Us – Level Design Breakdown [Video]. YouTube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oGM8lR9znDY

Francis, B. (2022, March 25). Take a peek inside the level design process of Horizon Forbidden

West. Game Developer. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/gdc2022/take-a-peek-inside-the-level-design-process-of-horizon-forbidden-west

God of War [Video Game]. (2018). Santa Monica Studio.

Half-Life 2 [Video Game]. (2004). Valve.

Horizon Forbidden West [Video Game]. (2022). Guerrilla Games.

Menzel, J. (2017, June 6). Level Design Workshop: A Narrative Approach to Level Design [Video].

GDC. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FhKjv7CPUqw

Skyrim [Video Game]. (2011). Bethesda Game Studios.

Smith, H. & Worch, M. (2010). What Happened Here? Environmental Storytelling [PDF]. GDC.

https://www.gdcvault.com/play/1012647/What-Happened-Here-Environmental

Stray [Video Game]. (2022). BlueTwelve Studio.

The Last of Us [Video Game]. (2013). Naughty Dog.

The Last of Us Part II [Video Game]. (2020). Naughty Dog.

Take Aways

Developed a deep understand of the tools available to level designers to communicate narrative

Developed communication skills, especially visual communication

Explored the approaches of many different games and developers to gain a clear picture of the level design process in narrative games.